What Makes an Advertising Jingle Stick?

Kit Kat, McDonald's and State Farm are just some of the many brands that have nailed iconic jingles - what is unique about their strategy?

It was an early Saturday evening - I was heading back to my home in the Mission neighborhood of San Francisco walking by a row of brightly-lit bars on Valencia Street. I heard the distant commentary of a basketball game while my phone tried to focus its gaze on the Google Maps directions.

The game cut to commercial and I suddenly heard the following sound:

🎶 Bah-da-ba-ba-bah 🎶

I didn’t have to look up from my Google Maps to know it was a McDonald's commercial. I briefly ignored it while the commercial moved on - but not for long. It came bouncing back into my brain a few minutes later.

I had no idea where I was navigating anymore. I had no idea where home was. Through the lights, sounds and stimuli of Valencia street, my brain was focused on a new mission: golden arches.

When McDonald’s released the “I’m Lovin It” jingle in 2003, they may not have known it was going to be the longest running jingle in McDonald's history. But this wasn’t their first rodeo. They had many hit jingles before - and it got me thinking about patterns.

Is there a science to which jingles get stuck in our head?

Why did that jingle stay in my brain on that long walk down Valencia Street?

More specifically, could we reverse engineer history’s top jingles?

To answer that question, I had to first find the consensus top jingles. This was no easy task - after a Google search prompted list after list of jingle rankings (Note: over sixty different jingles made at least one list!), I had to find commonalities and begin to narrow down the most appearances on ranking lists.

After some research, I consolidated the following targets:

I Wish I Was an Oscar Meyer Weiner (1965 - Oscar Mayer)

The Bologna Song (1960s - Oscar Mayer)

Stuck on Band-Aid (1980s - Band-Aid)

Plop Plop, Fizz Fizz (1970s - Alka Seltzer)

I’d Like To Give the World a Coke (1971 - Coca Cola)

Meow Meow Meow (1970 - Purina)

Give Me a Break (1986 - Kit Kat)

Double Your Pleasure, Double Your Fun (1986 - Wrigley’s)

Two All Beef Patties Jingle (1974 - McDonald's)

Like a Good Neighbor (1971 - State Farm)

I’m Lovin It (2003 - McDonald's)

(You can quickly watch them all here.)

At first glance, what’s crazy about this list is that some of these jingles are old - very old. The first one was introduced more than 50 years ago. Yet, you can still likely look at a lot of this list and remember exactly how the jingle sounds.

You may not remember what you ate for dinner last week but you fondly remember the tune to “Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there” or all the words to the “Give Me a Break” Kit Kat jingle.

How do these jingles, mere thirty second advertising spots, endure the test of time and infiltrate our brains?

Let’s explore the world of advertising jingle psychology.

Why Do Songs Get Stuck In Our Head?

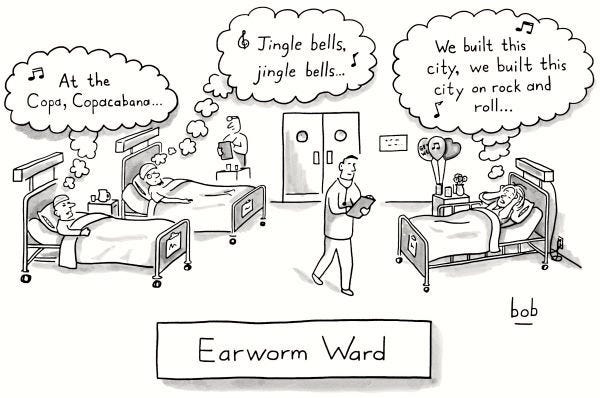

To understand advertising jingle psychology, we first have to understand why some songs get stuck in our head more often than others. There’s a science to it. It all starts with an important concept in cognitive psychology called earworms.

Earworms are simple snippets of music that get pushed into your brain almost subconsciously - the ones that pop into your head for seemingly no reason.

They’re stored under the umbrella of involuntary memory, a component of memory that occurs when cues encountered in everyday life evoke recollections without any conscious effort. We don’t deliberately go out our way to jam out to “Kit Kat” or the “Meow Mix” jingle over and over again - their mere existence baffles our neutral circuits.

Given the power of earworms to essentially infiltrate the human brain, it’s no secret that they have remained a source of interest for psychologists and neurologists for decades. Many scientists have pointed to the working memory model, developed by Graham Hitch and Alan Baddeley in 1974 as an important factor of earworm development.

Here’s an analogy for the working memory model: Imagine your brain as an office. There is one boss who controls everything with a bunch of employees scurrying around to give that boss different inputs - this is how you know what to see and what to hear.

This boss is known in the model as the Central Executive, a supervisory system that makes sure all the employees are working and continuing to send the boss inputs.

Now, there are a group of employees in charge of sound, led by a director called the phonological store. Like the boss, the director is very good at taking inputs but limited in capacity - he relies on a bunch of employees (articulatory rehearsal system) that function as an inner voice of sorts. When you’re going through a break-up or listening to an absolute jam, it will tell your brain how to think and feel.

It’s this same model that aids children in the development of vocabulary and adults in the acquisition of a second language. We start to recognize patterns in sound.

This is what makes earworms particularly frustrating. They disrupt this pattern. There’s no rhyme or reason to know exactly when a certain song will get stuck in your head - it could be triggered by the smallest things.

Not all song snippets are earworms though. Earworms are classified by a few standard themes:

They tend to be very short, no more than 15 or 30 seconds.

They tend to have a fast tempo and fairly standard melody, often with intense repetition like the riff in Smoke on the Water

They tend to have very simple lyrics or memorable quibbles - think something as simple “Who let the Dogs Out?”

The structure of the earworm forms the first part of a model we can use to explore why jingles become famous - the MES Framework.

What Makes Jingles Popular?

Committing something to memory alone is not enough to merit purchasing an item - so we have to pair memory with a couple other concepts to really understand jingle popularity. The MES framework is one way to explain the meteoric rise of some of the jingles we listed above - it consists of three easy parts:

Memory - Is this jingle likely to get stuck in your head?

Emotion - Is this jingle likely to form an association with an emotion?

Social Exposure - Is this jingle likely to get social exposure?

Let’s explore the jingles above.

Memory

For a jingle to really get stuck in our head, it needs to ideally be a perfect candidate for an earworm. Very simple lyrics, very short, and an uncomplicated melody.

Every single advertising jingle passes the sniff test above for length -- the longest jingle is less than 60 seconds total with the melodic component being an average of 10 seconds.

Further, many of them form melodic contours that are commonly found in Western Pop Music.

In a study by the University of London in 2016 on earworms, researchers pointed to songs with rising and falling pitches to be a good predictor of involuntary memory. Think of the song “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star”, where the first phrase rises in pitch and it begins to fall when you look at “How I wonder what you are” - numerous other nursery tunes (i.e. Wheels on the Bus) follow a similar pattern, which makes them very easy to remember.

Take a listen to both the Oscar Mayer Wiener tunes on the list - here’s an example of the Bologna song sheet music. The “O-S-C-A-R” rises, while the following line falls. Easy enough to fall into a kid’s vocal range and a melody that isn’t novel to them.

We like to think that we can outmaneuver kids - but our working memory model isn’t too different when it comes to earworms. Would “Ba dah bah bah” still get stuck in your head if it was all on the same note? Nope. The rising melody partly explains what makes it contagious.

The Oscar Mayer and Band-Aid jingles not only understand the value of having nursery-rhyme type melodies - their jingles are in fact sung by kids. The principle is simple: If a kid can sing it, your kids will be able to sing it. If your kids can sing it and sing it often, look out. It stands no chance against your feeble involuntary memory.

The lyricism in the jingles is also simple - nothing super complicated with “I Wish I were an Oscar Mayer Weiner” or “Plop Plop, Fizz Fizz” in the Alka Seltzer jingle. Nobody breaks any bones trying to sing “Break me of a piece of that Kit Kat Bar.” While copywriters can labor for days trying to find the best way to wordsmith a landing page or a newspaper ad - jingles benefit from the opposite: less is more.

In fact, one of the most dangerous earworms on the list has barely any lyrics at all - the Meow Mix jingle from Purina simply has a cat just saying the word “Meow” on top of a fun melody roughly sixty times. It’s simple enough for a kid to follow and simple enough to drive yourself crazy every time you look at your cat.

Emotion

The I’m an Oscar Mayer Wiener song is one of the most iconic jingles in history, first on the list above. It was as ubiquitous to kids in the 1960s and 1970s as the Yankee Doodle song.

But songwriter Richard Trentlage, who penned the jingle for an open contest, was not a hot dog connoisseur or a particularly ardent customer of Oscar Mayer. Instead, he was inspired by his son - who told his dad he wanted to be a “Dirt Bike Hot Dog”, a term to describe a cool kid back in 1960s America.

His son wanted to be cool - why not make being an Oscar Mayer hot dog cool?

The lyrics he scribbled out: “Cause if I were an Oscar Mayer Wiener, everyone would be in love with me” spoke less to a primal desire for hot dogs or even hunger. It spoke to the emotional gratification of social approval.

While many of us buy products because of a transactional outcome, the best jingles pull at our core emotional desires. The jingle for Coca Cola: “I’d like to Teach the World to Sing” is a perfect example of this - look at the lyrics below:

I'd like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony.

I'd like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company.

If you’re reading it on paper, you’re probably thinking… what does even mean?

But when you’re listening to the beautiful chorus of the folk group, the Hillside Singers, harmonizing and sending goosebumps up your spine, it doesn’t matter. You want to furnish the world with love, grow apple trees, dance through a field of flowers - and now you associate all those emotions with sharing a Coke.

In fact, this was such an effective advertisement for Coca Cola that more people remember the jingle version vs. the version that won the Hillside Singers a Grammy Award.

As you hear each jingle, you’ll see the pattern of core emotional desires. The “double your pleasure, double your fun” jingle from Wrigley’s became famous from a commercial where two guys eating Wrigley’s meant a pair of really attractive twins with a melody that includes“A double pleasure’s waiting for you”. The message was clear: eat Wrigley’s spearmint and you too can have the emotional gratification that comes with love and attraction.

The State Farm represents our core desire to feel safe. Dr. Pepper represents our core desire to have friends, camaraderie, and social approval. The Band Aid jingle represents our core desire to feel happy and healthy.

What’s crazy is that very few of those jingles say anything about the product. For someone unfamiliar with McDonald’s, there is very little they could get from “I’m Lovin It” as a tune - but it begins to help us associate Mcdonald’s with happiness and love.

They all tie to an emotion in our psyche and, working in tandem with the earworms, trigger that emotion for us. We might walk into a convenience store and be slightly more likely to buy a Coke - simply because it conjures up that vision of pure happiness.

Social Exposure

The last element of an iconic jingle is the social exposure. This one is the most self-explanatory element of the framework - natural social exposure and ubiquity will make jingles last.

How does social exposure grow?

In the 1950s and 1960s, this was largely driven by radio. In the 1970s and 1980s, this shifted to television.

When commercials historically favored 60-second ad spots over shorter ads, jingle makers were forced to get creative - instead of one sixty second ad, what if you could play a much shorter ad with a memorable earworm on repeat?

McDonald's is the cleanest example of this in 2020 - where even a 15 second spot with the familiar jingle can make you remember that it’s a McDonald's commercial.

Timing is also a big factor in social exposure - one of the primary factors for the Coca Cola jingle about world peace spreading came about because it was the early 1970s. Roger Greenway, one of the musicians who helped write the jingle, says as much:

“I think it was the flower power era, and most of America was tiring of the Vietnam War. The lyrics, although not overtly anti-war, delivered a message of peace and camaraderie.”

But commercials and radio spots alone aren’t enough - they have to work in tandem with user generated exposure. If people aren’t humming the jingles in grocery store aisles or walking down the street, the long tail of exposure is limited.

People want to be part of the in-crowd, a concept known as social proof in marketing. The more people that begin to sing jingles, the more others will be incentivized to imitate.

McDonald's capitalized on this concept of social proof in 1974, when they released their new Big Mac with a simple jingle - Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions – on a sesame seed bun.” It was a simple list of ingredients - but a tongue twister. It immediately sparked a movement of people proving they could say it all in one breath - and gave McDonald’s a breath of free advertising throughout the decade.

Of course, the elephant in the room is ad budget - and it certainly helps that the companies who made these jingles were world class brands with multimillion dollar budgets. Coca Cola alone spent $250,000 to produce its ad in 1971.

But as we’re learning today through TikTok algorithms and viral tweets - good content paired with the right timing can make even the most surprising brands spark in social exposure.

What Can Brands Learn?

While I wanted to end this piece on my theory of constructing the perfect jingle, you may have noticed from the list that very few popular jingles have been released after the 1990s.

The commercial licensing of pop songs has changed the landscape of jingles - in 1987, Nike licensed “Revolution” from the Beatles for a popular shoe campaign and it proved to be the start of a new revolution in advertising.

A majority of the commercials we see today use popular songs - but, despite the lack of originality and fun slogans in jingles, brands looking to use music can still using a lot of the same principles found in the MES Framework:

Memory: Is this a song with a hook that can easily capture our brain in 15-20 seconds? A recognizable melody? Something that someone can sing, hum, or snap along to?

Emotion: Is this a song that represents a core emotional desire? That helps someone associate a brand over time with an emotion?

Social Exposure: Is this a fun commercial, something that can be a fruitful sing a long? Something unique enough to break through the saturation of content shared today?

I do believe it’s still a golden age for brands and products to be synonymous with sounds - it’s hard for us to think of Are You Gonna Be My Girl? without imagining someone jamming out to an Ipod or Lady Gaga’s Applause without thinking of dancing hamsters and the Kia Soul.

In fact, we’re even seeing that some memorable lines in pop music can be ads - I’m sure some of you read “Double your pleasure, double your fun” in the jingle list above and immediately thought of Chris Brown’s song Forever, right?

Shocker, Chris Brown was actually a Wrigley’s spokesperson. That line was to re-introduce the slogan back into the mainstream.

A good jingle can do wonders for business -- it can save a dying brand, introduce a new item to a broader audience and rejuvenate a lackluster product. Even with original jingles now getting shifted in favor of licensed pop songs, the same principles that made advertisements popular can be evaluated today for commercials and ad spots.

While the nature of the advertising mediums have changed, human psychology hasn’t.

We’ll always react to sounds with emotional tugs the same - it’s all about brands finding the right formula.