Why Do We Love Mascots?

Some of our favorite household brands have used all sorts of mascots to help drive their brand visibility - why do mascots have such a big impact?

One of my favorite adrenaline rushes in life is the excitement that comes with moving into a new neighborhood.

I’ve spent the last couple of weeks in just that emotional space, exploring the nooks and crannies of my new home in SOMA. (For outsiders, SOMA is home to some notable tech headquarters, museums, and a baseball stadium that just so happens to host the best team in baseball as well as the best garlic fries in baseball. The latter is debatable and I will not say no to more garlic fry recommendations.)

Early one morning last week, I was walking up 3rd street to check out a new coffee spot when I stumbled upon a number of people setting up what looked to be a giant field of turf and a number of stages in a large alley.

It had all the allure of a magnificent concert with all the unceremonious touches of a music festival.

Stands and meticulously crafted kiosks flanked hammocks and bean bags. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted a large brown sign that told me everything I needed to know about this revelatory consruction: Dreamforce National Park.

Dreamforce, a conference thrown by Salesforce, is often known as the Super Bowl of software and in a normal year, one of San Francisco’s finest attractions. While this year’s conference wasn’t selling out hotel rooms or inviting mosh pit crowds waiting to catch a glimpse of Michelle Obama, Salesforce worked to make it live with a smaller crowd and an event hallmark: dancing mascots.

Astro, little Einstein, and Codey the Bear were among the Salesforce mascots who made an appearance, pumping life into the Friday morning slumber of the event.

Salesforce is one of the thousands of companies that use mascots in their branding and possibly one of the most successful ones in the B2B space. But watching this dance (seriously, how adorable is the Einstein?) had me thinking about the history of mascots in marketing overall.

Consumer brands have had mascots for decades. Do they actually make a difference? Should more brands be like Salesforce? What really makes for a good mascot in general.

I explore all that and more this week - the psychology of mascots, marketing, and brand perception.

Why Do We Love Mascots?

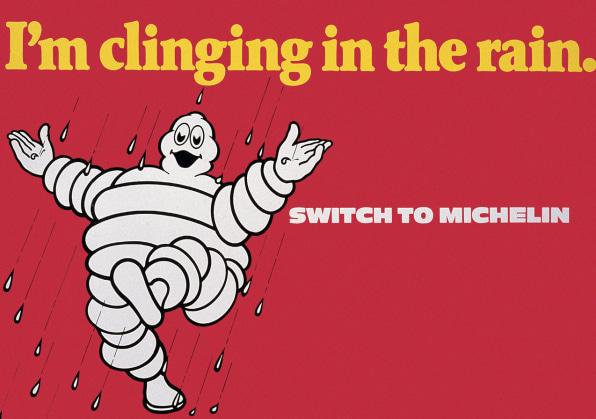

Conceptually, our understanding of brand mascots goes back decades. The honor of the oldest perhaps goes to a mascot we know today that was born in 1898.

Named Bibendum (from the Latin phrase now is the time to drink), the Michelin Man was born from the vision of Andre and Edouard Michelin, who came across a large stack of tires that they felt resembled an armless man.

The early century brought us some favorites. The Jolly Green Giant in 1925. Snap, Crackle, and Pop in 1936. Miss Chiquita Banana in 1944. The Trix Rabbit in 1957. The Morton Salt Umbrella Girl and Chicken of the Sea Mermaid recently celebrated centuries carrying their brands.

In the field of cereal alone, we can count a handful of mascots we’re all familiar with: Lucky the Leprechaun, Toucan Sam, Cap’n Crunch, and more.

They all have stories and hooks. Talk to anyone who grew up in the last 25 years and they could probably detail the agonizing tale of the Trix Rabbit who constantly gets stiffed.

Cereal gives us the first hint of why mascots work so well in advertising: The mascots aren’t just meant to work as vehicles to make ads brighter and more colorful. They can be meant to work as metaphors.

Take the mascot for Honeycomb Cereal, for example, a creepy marsupial type animal who goes absolutely apeshit for cereal and whom children transform into as soon as they start to crave it. According to the Breakfast Cereal wiki (yes, this is a real thing and quite wonderful), the mascot’s name is Crazy Craving. What’s more, it’s essentially supposed to be essentially an anthropomorphism for hunger.

It’s hard to imagine you’ll be hungry, break your pencil in the middle of a test, and turn into a full-fledged hyperactive deviant just because you want cereal.

But, the mascot suddenly allows you to associate a visual experience with what is otherwise a relatively mundane feeling.

Take the Trix Rabbit as well, a fanatical anthropomorphic rabbit who has a somewhat unhealthy obsession with Trix cereal. Positioning the rabbit as some sort of simple outsider who constantly gets denied the cereal again adds a visual experience to something that is more abstract, like rejection.

If you hate seeing the rabbit get denied over and over again and want to avoid that experience, the best way to do that is simply to eat some Trix. (Side note, I watched so many Trix commercials ahead of writing this and I honestly empathize with the rabbit a bit more these days. The dude has literally climbed mountains and won competitions just for a bite of cereal. Just give him a fucking bite.)

But adding a layer of experiential association to feelings is only one part.

The other is a concept I touched on a bit in my Super Bowl piece about what makes effective commercials: creative juxtaposition.

Advertising execute Leo Burnett, whose agency created some of the well-known characters of the 20th century (including Tony the Tiger and the Marlboro Man in the 1950s) has an amazing quote I love that touches on some of the effectiveness of mascots:

"The secret of all effective advertising is not the creation of new and tricky words and pictures, but one of putting familiar words and pictures into new relationships."

In essence, creating two things that don’t normally belong together and putting them together in a way that introduces a new creative relationship.

Juxtaposing things in a creative manner.

On one hand, we have a preference for the familiar. On the other, we have a thirst for the novel.

Mascots often give us the best of both worlds.

In the real world, Britsh geckos don’t sell insurance. Jugs of flavored drinks don’t run into walls. Toucans don’t go on adventures to dig up colorful cereal.

With mascots, you can effectively stretch any bounds of physics and artificial parameters to make these stories memorable.

There’s perhaps even another layer on top of just the creative juxtaposition that serves as a big draw for these animalistic mascots: humanization.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how anthropomorphism, the innate instinct for us to give inanimate objects and animals human-like characteristics, makes SMS marketing particularly compelling.

But the real deal isn’t for SMS: it’s for mascots.

In a Better Copy piece about the psychology of mascots, strategist Weston Gardner discusses how having a character for your brand doesn’t just matter in terms of physical attributes; it also matters for emotional ones.

You can’t necessarily rehabilitate a scandal-ridden executive in your company easily to improve brand perception - but your characters are all malleable.

You can add more favorable thoughts and attributes to the character over time. You can update their stories in the canon, give them childhood stories, give them motivations and desires. If you’re feeling really funky, you can even kill them for a heroic sacrifice.

In a world where creative consistency becomes a challenge, it stretches the limit of what you can do with brand spots.

In the 1970s, once Tony the Tiger had become quite popular, his legend began to grow.

He was given an Italian-American nationality, a family, and newer advertisements targeting his more human side. For Mothers’s Day in 1977, he was given a spot where he visited his mama, giving her flowers and sitting down for breakfast with her. In perhaps the most shocking twist of a mid-century commercial storyline, they ended up having Frosted Flakes.

Why do we like human qualities?

In an Adweek piece about the neuroscience behind mascots, author Spencer Gerrol flagged a simple explanation:

We understand the most about human behavior, we are motivated to explain the behaviors of others and we thrive off of social connections. While we have a tendency to anthropomorphize many things, we actually have an easier time giving life to something when it looks more human.

In his piece, he shares a more subtle example of this that we may see often - the Pixar lamp. The lamp jumps onto the screen, looks around in wonder, and then takes a fairly homicidal turn that involves destroying one of the Pixar letters before stopping.

While it’s very rare for us to imagine a lamp as a human, just physical qualities and activities make us believe it’s not too far removed from the ordinary to repel us.

Pixar’s animation, Luxo Jr, takes this further. In just two minutes, it tells the story of a mother lamp and a baby lamp, the mother lamenting as the baby attempts to jump onto a small ball.

The baby’s excitement and mother’s concern will indeed have us empathizing even with household appliances.

Final Thoughts

A brand mascot can certainly breathe life into your brand and it’s a simple value-add for your marketing and design materials.

When Salesforce began to market the Dreamforce conference, it was easy for them to plug any of their mascots into a different human situation for an asset, using a product of one of their sponsors or simply even participating in the conference itself.

But this doesn’t work everywhere.

It’s easy to imagine why mascots are popular for food brands - they can consume the product (Minus the poor rabbit, I’m still bitter) or get into wayward adventures that make for fun commercial spots. When it comes to an especially commoditized product like cereal, it’s almost necessary to have it for unit differentiation.

But is it worth it for every product?

Of course, even consumer products can have their own failures.

Remember Waldo The Wizard? Of course, you don’t. General Mills swapped him with Lucky as the next mascot for Lucky Charms and it did not go well. Removed in less than a year, he’s a simple footnote in cereal mascot history.

But more so than just actual character flubs, there is a larger school of debate around whether it’s as easy for (non-Salesforce) B2B companies to have mascots.

My friend Jason Bradwell (who writes a great B2B newsletter) actually wrote a bit about the power of Salesforce mascots back in December and mentioned some great reasons for brands like Salesforce to have a mascot: value in storytelling, emotional connection, and visual stimuli to associate with the brand.

While I agree with all of that, there is a darker side: Education, personification, and promotion become much harder to do through a mascot in a complex product world.

Clippy, from Microsoft, was famously ridiculed. But in Clippy, we see an unfortunate martyr for a larger narrative around decision support mascots.

They can make a brand memorable, sure, but if a decision-maker is going for a more logos route to persuasion (facts and logic), it remains to be seen whether a cute bear with a backstory or an anthropomorphic paper clip can help them get there faster.

Ultimately, one of my tenets is that your marketing becomes enticing when you give someone the urge to disagree.

Take this framing: Few people have strong opinions on enterprise CRM platforms. Lots have strong opinions on animals, household appliances, and robots.

The minute you introduce a mascot into your marketing mix, you tap into the world of humans that will suddenly draw your brand into a fight - what might even be an easier fight than actual business.