Swarm Deserves a Redemption Arc

My quasi-romantic and hopeful future for Foursquare's check-in app.

Like any tech-addled millennial in the past decade, I’ve often been asked which apps on my phone I love more than others.

Some of the answers aren’t so surprising. But there’s always one that manages to throw people off.

It’s an app that I’ve used for more consecutive days in the past decade than Twitter, Spotify, Whatsapp, Facebook, and even Instagram. An app that has managed to surpass my longest Snapchat streaks, Amazon binges, and aspirational Kindle reading challenges. An app that I’ve managed to find in my deepest states of drunken stupor and strangest bouts of sleeplessness and delirium.

Still, it’s sometimes hard to explain why I still use Swarm.

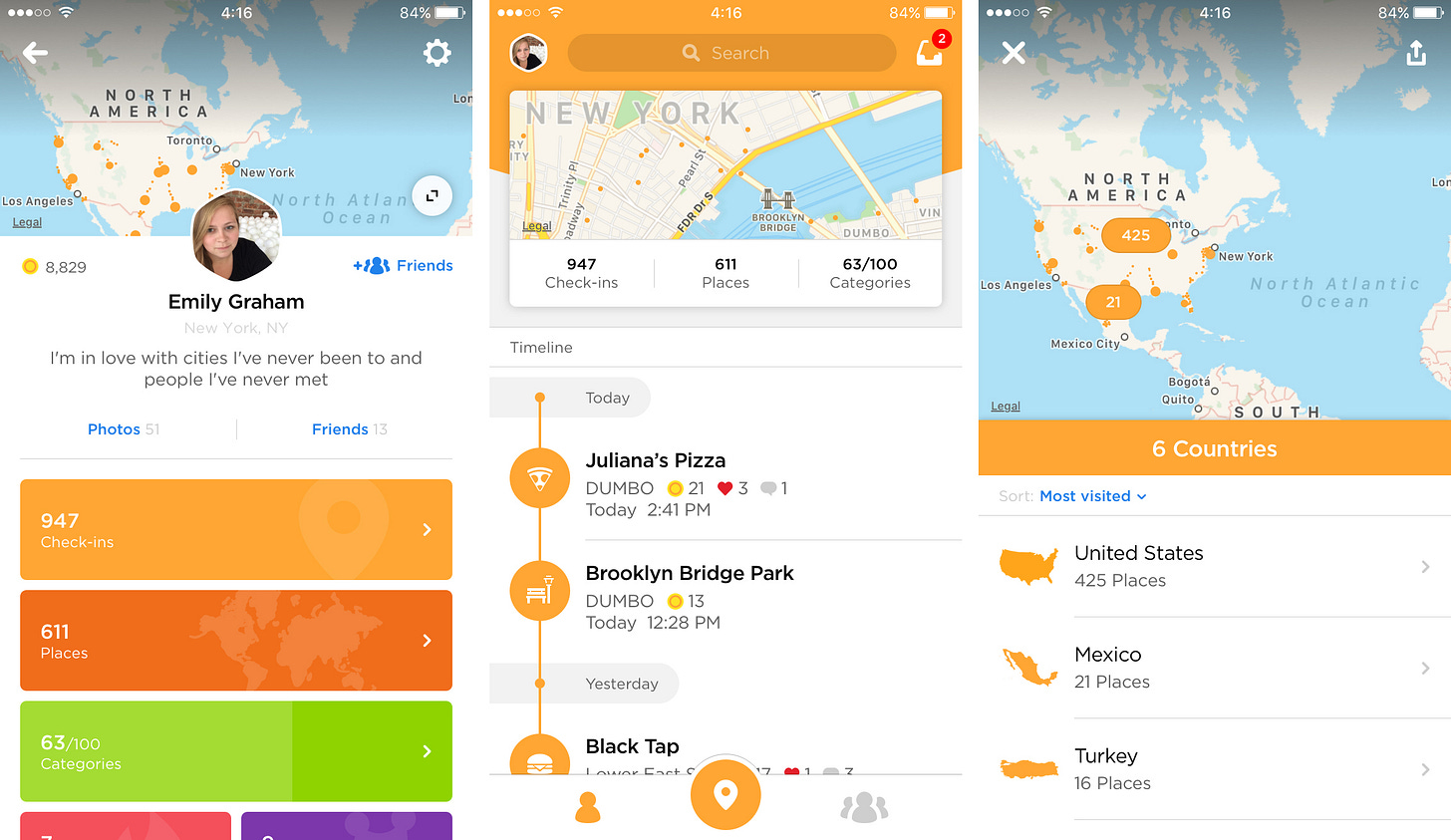

To the uninitiated, Swarm is simple in its premise: It’s an app where you can check in to different places on a map powered by Foursquare’s massive location databank and get worthless coins in return.

But to its loyalists, Swarm is more than an app: it reflects our deeper nature.

The casual meandering from an office to a grocery store, the conquest of restaurants to find the perfect breakfast sandwich in your city, the precision with which you choose to go off the beaten path on your travels. Safeway or Trader Joe’s? Italian or Ramen on a random night out? Pat’s or Geno’s in Philadelphia? Neighborhood dive or well-lit signature cocktails?

Swarm is who we are. Micro-decisions scattered across a map that slowly unblurs over time to paint a mosaic of our desires. In the same way that the Mirror of Erised shows our deepest desires, Swarm confirms how they’re manifested.

Give me someone’s Swarm history, and I’ll learn quickly how they live their life.

We often talk about deeply integrated product market fit in tech, and Swarm’s WAU chokehold is almost laughable for an app with no major product releases or media traction in practically five years.

To other Swarm users, checking in is about as natural as brushing your teeth or doing laundry every week. Hanging with another Swarmer and checking in together is as cherished a memory as doing a collective group shot. When I went to Portland for a friend’s bachelor party a couple of weeks back, three of us, who were all dedicated devotees of Swarm culture, took turns checking each other in on the app. Being the first one to do the check-in for the rest of the group was a badge of honor—a perverse ritual to the rest of the world but a regular occurrence in Swarm Land.

You would think that an app with such romantic appeal and cultish behavior would somehow be attracting headlines and courting rankings as much as any other habit-loop-induced app out there.

But the diminishing relevance of Swarm is somewhat of a mystery.

The history starts with its parent app, Foursquare, which many might remember as a location-based social networking tool that was ready to take Facebook and Twitter’s lunch. Foursquare started with three big bets:

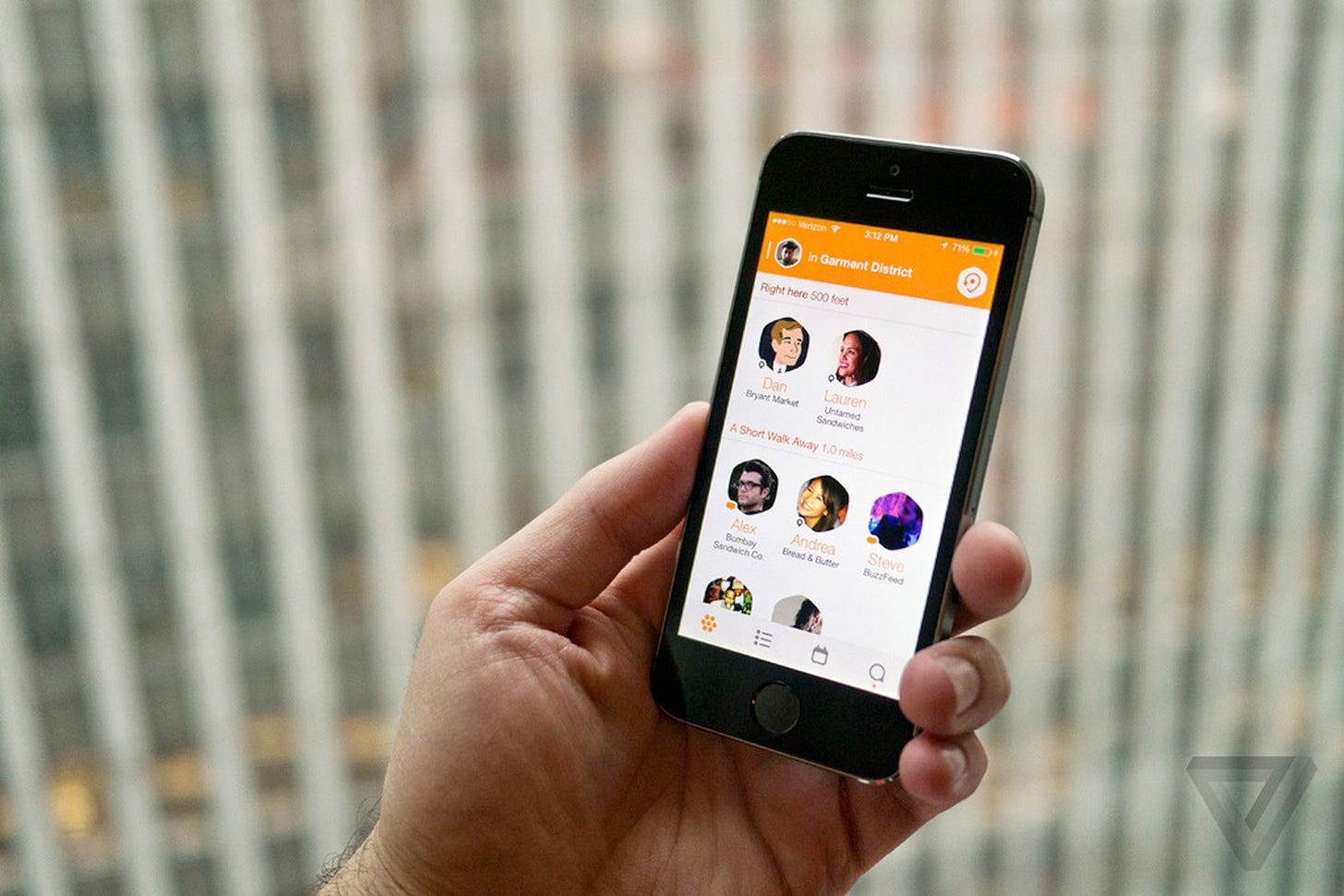

People were interested in what their friends were doing in real-time

People were interested in crowdsourced information about cities

People value gamification as part of their daily activities

The real-time location check-ins and quirky achievement badges quickly made it the darling of 2009’s SXSW and, at one point, even the 3rd ranked app in the app store.

Then, as quickly as its moat grew, battalions came at Foursquare in many directions.

Competitors like Yelp and Google Maps would scale their crowdsourcing capabilities, complemented by Instagram scaling city guides from the media to new heights. Worse, there was always an underlying fear of privacy. Did people want to share their real-time location? Was it worth Bob knowing that you were having a sandwich at Molinari Delicatessen if the rest of the world knew it too? It seemed like gamification was still an opportunity, but could it survive the onslaught of attention-demanding apps to come?

Foursquare had an identity crisis. It couldn’t win social networking. Could it win travel? Could it win commerce?

Slowly though, it realized it was sitting on an opportunity all along—the data.

With more than 3 billion visits monthly and 55 million monthly active users by the late 2010s, Foursquare was raking in location data at an incomprehensible scale. As the company expanded upon perfecting its location-tracking technology, it became useful to a whole new audience. Other companies.

Foursquare did what every consumer company with an identity crisis eventually does: They became a B2B platform.

With data as its bread and butter, Foursquare pivoted into providing companies with global location data that powered geofilters in Snapchat, tagged tweets on Twitter, and helped find address data in Uber and Airbnb.

By all accounts, the pivot has been successful (In Q4 2020, the company had its first profitable quarter), and Foursquare even rocked a rebrand to honor its slightly modified mission.

But the rebrand still left questions for Foursquare loyalists.

(By Foursquare loyalists, I mostly mean me. By questions, I mean one question.)

What the hell is happening with Swarm!?

While there was some murmur about Swarm pivoting into a “lifelogging” app beyond social networking, there was no real movement toward what a broader future for lifelogging could look like. Swarm became a mere funnel for Foursquare’s bigger data-building ambitions, the forgotten child now subsidized for mere existence.

To quote Bernardo Montes de Oca in his piece for Slidebean:

“Swarm, yes, it still exists. But so do people who sell ink ribbons for typewriters.”

In the land of consumer technology, Swarm is nothing but a whisper. Even today, a quick search will yield more about honey and Donald Glover’s new TV series than the once-popular logging app.

But something happened quite recently that makes me wonder if Swarm’s story is finished.

Gowalla, the once-popular location networking app that met its demise in 2012, returned for a redemption arc. Relaunching at SXSW (sensing a theme here), the team is looking at renewing a thesis around location-based networking that killed most of its incumbents a decade ago. What changed?

CEO Josh Williams acknowledges that a lot has, starting with scale.

Williams says one of the things that has changed is the sheer scale of mobile users, which means that even if only a small percentage of your overall user base wants to pay up, you stand a chance of building something that can successfully monetize in this way. Location-based networking app Zenly, which Snap acquired and then shut down, much to the chagrin of its many million active users, is a great example of an app that had that kind of scale in the same space Gowalla is targeting, he added.

Williams adds a myriad of other reasons: the pandemic, larger social networks losing prominence, desire for human connection, and more.

But while the thesis of real-life, real-world-based social networking is getting new legs, I can’t help but think there’s clearly a missing pawn: Swarm.

Having tried Gowalla in the past week after a decade of Swarm usage, I found the experience nice. It’s not as pre-populated as Swarm but I do think it will accomplish what it wants to do for location tracking and check-ins effectively with scale.

But this is where I would love for the sleeping beast of Swarm to awaken.

It’s true, Foursquare doesn’t need the money as much as a new startup and they’re likely tired of playing the game they’ve struggled to keep afloat for so long.

What I can imagine is that there is a world beyond lifelogging in a silo that is more interesting than location-based networking.

Instead of connecting with your friends just because they are close by (let’s be honest, texting probably works fine for this), what if you could take the accumulation of their check-in history, preferences, and life routines to create more of a social tapestry?

Put people into larger categories based on how their Swarm works?

What if you could tap into lifelogging as a potential springboard for friendship, romantic relationships, or food recommendations based on someone who has similar Swarm tastes as you?

Imagine a Swarm personality score. Swarm culinary taste. Swarm neighborhood vibes. The mayorships and loyalty check-ins as signs for businesses. So many indicators of you who are that could resonate with others.

I do think a lot of Gowalla’s thesis makes sense. We do want human connection. We do want things to be more real. We are at a point where we’re definitely on our mobile devices enough to create a base tremor of a network effect for any app.

But is it that important for these connections to happen offline in real time?

Or more important that our locations feed into a bigger picture of who we are?

If Swarm doing nothing meaningful in the short-term to its app hasn’t deterred me much, I can only imagine a future where it has the sweet and soulful redemption arc it deserves.

At the very least, it can give me a nice little kickback for all these fake coins.

Yes!! I’m a Swarm superfan, too. Would love to see this redemption arc 🙌

Your assessment on Swarm is spot on.